For a man who describes himself as having once been a “small welterweight”, the middleweight debut of Georges St-Pierre, which culminated in a third-round submission of UFC 185lb champion Michael Bisping on Saturday (November 4), was a sight to behold.

It came four years after his last fight – a tight and controversial decision win against Johny Hendricks at welterweight – and ended decisively, inside the distance (his first win of this kind since 2009). If this alone is cause for celebration, consider, also, the fact his striking looked crisp, he landed overhand rights at will, he secured takedowns, he appeared strong at the weight, and he attacked Bisping with purpose and spite from the get-go. In short, any fear St-Pierre, the former UFC welterweight king, would be rusty, slow and undersized was allayed pretty much immediately.

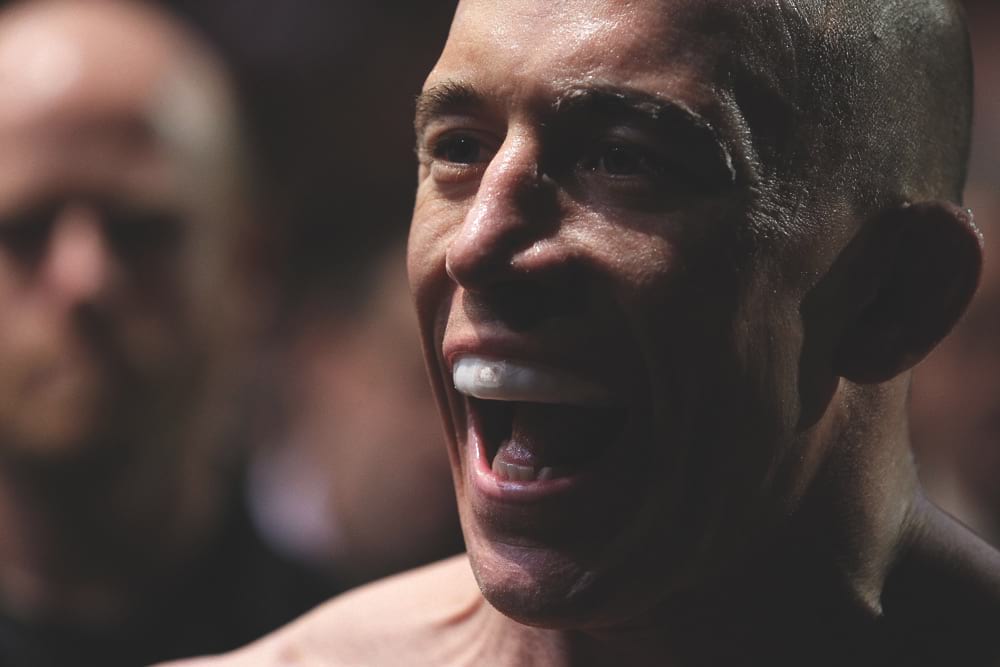

Still, there were shaky moments here and there. In round two, St-Pierre appeared to slow down, feel the pace, and all of a sudden become wary of the fact he was embroiled in a five-round championship fight. Yet no sooner had anxiety started to set in, and fans prepared themselves for a great unravelling, than the French-Canadian rocked Bisping with a hook and promptly submitted him with a rear-naked choke, holding it tight until the middleweight champion, refusing to tap, passed out.

In finishing the fight, St-Pierre, already considered the greatest welterweight of all-time, became a two-weight UFC champion, and now has the opportunity, if he so chooses, to create a second reign of terror 15 pounds north. There are, potentially, fights with Robert Whittaker, the interim champion, and former champions Luke Rockhold and Chris Weidman in his future. Or Jacare Souza. Or Yoel Romero. Conversely, he may decide to dump the middleweight belt, considering it mission accomplished, and scurry back to welterweight having knocked about with the big boys for an afternoon.

Who knows?

Even Georges St-Pierre, the 35-year-old responsible for making the decision, seems unsure where he’ll eventually end up. On the one hand he has bemoaned the fact he was undersized as a welterweight, and on the other hand he has frequently reminded those who doubt his stature as a middleweight that this move has been anything but spontaneous or reckless and has, instead, been planned and well thought out, his new middleweight body, one Bisping deemed soft and fleshy before their fight, sculpted over the course of a number of months.

Even so, to listen to St-Pierre talk, especially after Saturday’s win, you’re left with the feeling he’s a welterweight now begrudgingly trapped inside the body of a middleweight. He sounds like a man who knows he’d be best suited in the 170lb division, battling the likes of Tyron Woodley, Robbie Lawler and Stephen Thompson, but made a commitment to fighting Michael Bisping in 2017, a matchup he cherry-picked, and is now stuck between a rock and a hard place – which is to say blown up to middleweight dimensions but aware of the fact he may be dwarfed when facing the crème de la crème of the middleweight division.

St-Pierre has no such concerns at welterweight. He had fourteen UFC title fights at that weight and effectively cleared out an entire division. He took welterweights down whenever he wanted to take them down and he kept them there for as long as he wanted to keep them there. He seemed, from 2007 to 2013, as close to invincible as any fighter could hope to be; the envy of an entire weight class.

At middleweight, however, in an era full of versatile fighters for whom takedown defence is no longer a foreign word, this success will likely be tougher for GSP to replicate. Bisping, for example, the first middleweight St-Pierre has faced in 15-year pro career, was able to scamper to his feet following numerous takedowns – a rare sight in St-Pierre’s welterweight days – and, even when on the bottom, was seemingly comfortable, content to nullify St-Pierre’s ground-and-pound and cut open the former welterweight champion with well-placed elbows. There was certainly no suggestion St-Pierre was the ferocious, unstoppable force – the takedown machine – he was at 170lbs. No indication whatsoever, in fact.

Going forward, that would be a worry for Team GSP. If he can’t take opponents down and keep them there – when tired, when hurt, when out to stifle, when looking to pocket rounds – his overall threat level and all-round efficiency is severely depleted. He becomes a kick-boxer – a very good one, admittedly – who, in all likelihood, concedes height and reach to a bigger, heavier opponent. He’s depleted, handicapped. He gives the rest of the field a chance: a chance to get away, a chance to hit him, a chance to beat him.

Then again, isn’t this all part of the challenge, and therefore relevant to GSP’s quest for greatness? After all, it’s one thing to return to his natural habitat and pick picking up his old title, one he held for some six years, yet quite another thing to establish himself at middleweight and take over there. Perhaps his attempt should be greeted not with scrutiny and cynicism – “He’s only at middleweight because he thinks Bisping is an easy fight!” – but with admiration and respect, viewed as the move of an older fighter out to confound the doubters and prove people wrong.

The truth, one suspects, lies somewhere between both points of view. No doubt the lure of Bisping and a UFC title in a second weight-class was key to GSP’s decision-making. He sensed an opportunity, saw what he perceived to be a beatable champion, one whose style would present him few problems, and exploited a fast-track to the top again, following four years out in the cold. It was, in light of this, a business decision as much as one rooted in sport and competition. But we must also not forget that many believed Bisping, riding a five-fight win-streak, was in some ways the worst kind of opponent for a returning Georges St-Pierre. Bigger, stronger, blessed with underrated takedown defence and unmatched stamina resources, the view of the contrarian was that ‘The Count’ could show St-Pierre just how far the game had progressed during his four-year absence, and do so by bullying and outlasting a perfectionist whose preparations, Bisping claimed, were anything but perfect.

It never happened. In the end, St-Pierre was simply too good, and the move to middleweight, on that basis, has proven a good one. It allowed him to jump the queue, snare Bisping before anyone else got there first, and add a second UFC title to his collection. It has also provided a fresh lick of paint to his name and reputation, introduced him to a new audience, and jogged the memories of those who had forgotten his greatness.

But that’s only step one. Steps two and three could be trickier. The longer he hangs around, as an artificial middleweight, the greater the risk becomes. Bigger men will start to circle. Intelligent men, younger men, tougher men; men who hit harder than those who punched him at welterweight. It could get rough.

It’s maybe then, and only then, Georges St-Pierre, the new UFC middleweight champion, will come to realise he’s unquestionably one of the greatest mixed martial artists of all-time, but no middleweight.