You take a pair of boxing gloves, weighing anywhere between eight and sixteen ounces, and the first thing you do is squeeze them and feel the padding. It’s instinctive. You could be about to put them on your fists with the intention to train, spar or fight, or you could simply be eyeing them up in a store. But, whatever the reason, once those gloves are in your hands, you will take comfort and reassurance from this process. From the padding. From the protection.

You may even do similar with a head guard, that additional protective measure used both in sparring and formerly in amateur contests. That also has padding. That also carries with it a veneer of safety that allows you to suppress misgivings and stand in punching range with another human being intent on doing damage. But it’s only punching, you tell yourself. It’s not mixed martial arts, where they can punch, kick, elbow and knee you wherever and however they like, where they toss you to the floor, where they can manipulate joints and break bones. It’s not dangerous like that. Not scary like that. Look at their gloves. Those two-ounce gloves, as good as bare-knuckle, and the ferocity with which they use them to whack grounded opponents. Imagine doing that.

But don’t be fooled. David Zinczenko, writing for the New York Times in 2011, put it best when he called boxing paraphernalia “the equivalent of poorly designed sunscreen – ‘protection’ that allows athletes to submit to even greater levels of punishment.” Truth is, though sometimes referred to as the sweet science and the noble art, boxing is also responsible for the deaths of men and women – far more of them, in fact, than can be attributed to MMA, a relatively new sport but one misunderstood due to its brutal image and reputation.

Indeed, according to the Manuel Velazquez Boxing Fatality Collection, which began tracking boxing deaths in the 1940s, there were 339 deaths resulting from head injuries in boxing matches from 1950 to 2007; more recently, it shows 60 deaths associated with professional boxing matches from 1998 to 2011 (the last year available). The same collection, for argument’s sake, counted four MMA-associated deaths from 1981 to 2007, but only one of those, the death of Sam Vasquez, was the result of injuries sustained in a regulated contest.

The numbers support MMA, then. We know that much. But what we also know is time has yet to cast its judgemental eye upon MMA the way it has boxing. It’s why the boxing fraternity nod their heads with a just-wait-and-see expression on their faces. It’s why they point to a clip of a mixed martial artist being grounded-and-pounded, their face like something on the receiving end of a butcher’s cleaver, and question what their quality of life will be when they’re retired and attempting to one day tell the grandkids all about their career. Give it time, they say.

What we do know is this: in November 2015, researchers at the University of Alberta’s Sather Sports Medicine Clinic discovered that although MMA fighters are more likely than boxers to experience minor but visible injuries like bruises or contusions, they are less likely to receive long-term injuries such as concussions, fractured eye sockets and broken bones. Dr. Shelby Karpman, a sports medicine physician and the study’s lead author, explained: “You’re more likely to get injured if you’re participating in mixed martial arts, but the injury severity is less overall than boxing. Most of the blood you see in mixed martial arts is from bloody noses or facial cuts; it doesn’t tend to be as severe but looks a lot worse than it actually is.”

Considered the largest study of its kind in mixed martial arts vs. boxing injuries, researchers analysed the post-fight medical data of 1,181 MMA fighters and 550 boxers who competed between 2003 to 2013 in Edmonton, Canada. What they found was 59.4% of MMA fighters and 49.8% of boxers suffered some form of injury on fight night, but that 7.1% of boxers lost consciousness or suffered more serious injuries compared to 4.2% of those competing in MMA.

“When you’re looking at damage and injury, it really depends on what type of injuries you’re talking about,” says Trevor Wittman, a veteran boxing and MMA coach who now spends most of his time teaching the latter. “Because of the repercussions of the head attacks in boxing, it was, to me, clearly the more dangerous of the two. But, at the beginning, I looked at MMA and thought, wow, that’s brutal. I thought it was way more dangerous than boxing.”

Wittman was once surrounded by pro boxers, including the likes of three-time junior middleweight world champion Verno Phillips, and even allowed them to live with him throughout training camp, so keen was he to monitor their progress on a daily basis. He’d cook for them. He’d run with them. He became aware of the signs. The good days; the bad days.

“I would always have my boxers, after 10 or 12 round fights, pissing blood and not knowing too many of the details of the fight,” he recalls. “I’d get the same old questions. ‘Did I get knocked down?’ Even when they won the fight, they were confused.

“If you think about it, it’s not so much the fight itself. It’s the training, the sparring. Thankfully, I was a guy who didn’t have my boxers do lots of sparring. I was criticised once for only putting them through forty rounds of sparring prior to title fights. The average was something like 120.

“But, if you’re doing hard sparring in boxing, you’re going ten or twelve rounds three or four times a week. You’re also facing a fresh guy every round. You’re getting rocked and then coming back two days later. That’s a problem. It was clear to me, over time, that boxing was much more traumatic to the head than MMA.”

Wittman has witnessed the trauma from every angle. He has sparred in 16oz boxing gloves and felt “cloudy in the head” afterwards. He has comforted the blood-pissers. He has, in his role as an MMA coach, found himself shocked by the sight of elbows and knees connecting with faces. He can still recall how his heart raced the night he cornered Nate Marquardt, one of his fighters, in a bout against Ivan Salaverry in 2005. Green and wide-eyed, he remembers the sound of the boards under the fighters’ feet and how it sent a shiver down his spine. “I was like, oh my god,” he says. “But I was never thinking, oh, this is so dangerous. I don’t think anyone can make that assessment until you’ve spent years in the sport.”

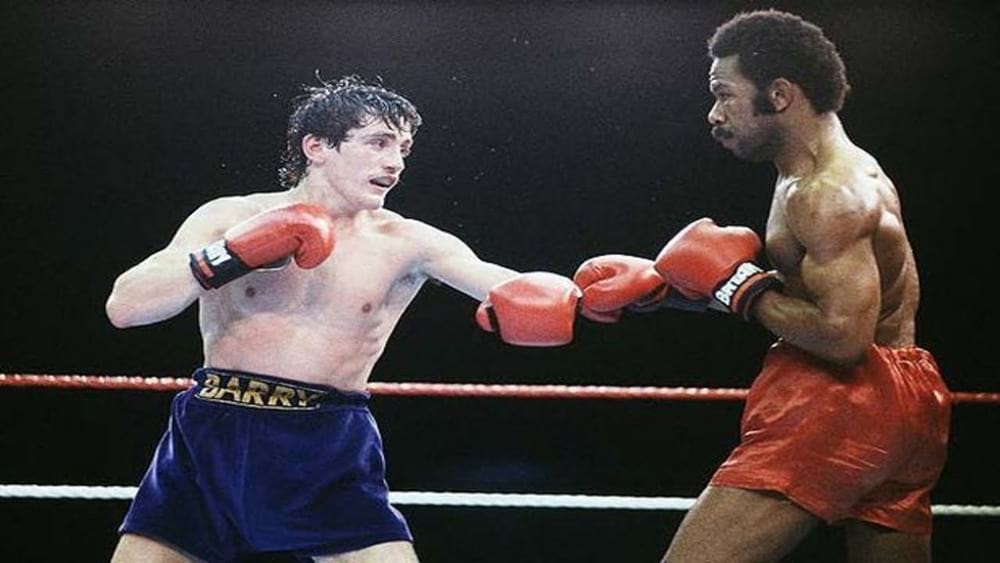

A boxing advocate through and through, former WBA world featherweight champion Barry McGuigan hasn’t experienced both sides. What he has experienced, though, is the feeling of hitting a young African opponent with a straight right hand, seeing him fall to the canvas, seeing his eyes roll back in his head, and knowing, there and then, he might never again wake up. Tragically, Young Ali, a 21-year-old Nigerian with whom McGuigan exchanged punches in 1982, never did. It’s one experience McGuigan wishes he could erase. Yet, equally, it’s one that gives his insight gravitas.

“You get more brain damage and tearing of membranes inside the skull from boxing than in UFC (MMA),” he says. “They don’t punch as hard. They’re not taught to punch correctly. They’ve also got to grab and do other things. They use different muscle groups. They’re not as free in the shoulders as boxers are. They’re not punching as hard and there’s not as much protection for their hands; with padded gloves and properly wrapped hands, you’re doing far more damage.

“The trauma, I believe, is far greater in boxing. It’s better to be knocked out quickly than to withstand a sustained beating. That’s when the damage is done, when a fight is long. That’s when the brain is turning and being knocked around the skull.”

The fighters, those in the game, explain it best, of course. They are the ones who receive the blows. They, unlike the researchers, are the ones familiar with the feeling.

“There’s not a death in boxing every year, there are deaths – plural,” adds Wittman. “In MMA, it’s so hard to even hear of a death; there have only been a few. It’s later in life, though, that the CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) shows up and you can really determine the extent of the damage.

“What stands out to me now is that in a boxing match you wear shoes and shoe companies are making their shoes as grippy as they can for a canvas. Then you’re always at close quarters. You don’t have to jump to jab. You’re right there. You’re in the pocket. And there are combinations being thrown. Multiple blows. You’re forced to fight on the inside. In MMA, you’re in and out and typically four or five feet away. It’s one punch at a time and the fight is stalled a lot more through clinch work.

“In boxing, if you get rocked and dropped, you get up on autopilot and continue fighting even though you don’t know what you’re doing. In MMA, if you get dropped and aren’t protecting yourself, the fight is effectively over. It ends quickly. There are not many knockouts in MMA where you see a guy laid out for a long period of time. There are plenty in boxing.”

Frank Mir, a former UFC heavyweight champion, believes he knows why. “We don’t have a standing eight-count in our sport, whereas in boxing you get rocked and then they’re going to stand you up and you’re going to try to continue after eight seconds,” Mir told ESPN in 2010. “You’ve already been dropped – doesn’t that mean you already suffered a concussion? That’s why we have a better safety record than other combat sports.”

There’s that word again: safety. According to a 2014 study in the American Journal of Sports Medicine, safety is one-third of professional mixed martial arts matches ending in a knockout or TKO. It’s 108 of 844 UFC bouts between 2006 and 2012 ending via knockout and another 179 bouts ending in a TKO, usually after a combatant was hit in the head five to 10 times in the last 10 seconds before the fight was stopped. Safety, therefore, is all relative.

Try telling the family of Joao Carvalho that MMA is the safer option. His death in April 2016, two days after a fight with Irishman Charlie Ward, shook the sport to its core. Worse, it opened the floodgates for MMA to experience much of what boxing has faced for centuries. “Legal killing,” was how The Irish Times’ boxing correspondent Johnny Watterson called the fateful bout, adding that MMA “crossed the line”. Michael Ring, meanwhile, the Junior Minister for Sport, told RTE Radio One’s Today programme, “I like the boxing, but this other sport, it doesn’t fit for me.”

For some, it won’t ever fit. The image is too gruesome, the reputation too dark. But, misconceptions aside, the great thing about mixed martial arts is it’s a sport young enough to not only learn from its own mistakes but also those of others. It’s realising, for example, what boxing has done wrong. It’s understanding what safety, within the realm of fight sports, actually means. Best of all, mixed martial arts, through improved drug testing and injury prevention measures, now knows it’s less important to be ‘as real as it gets’ and more important to distinguish itself as being as safe as it gets.

*** This feature appears in the October 2017 issue of Fighters Only magazine ***