Eight years ago I was tasked with ghostwriting UFC.com blogs for the cast members of The Ultimate Fighter 9: United States vs. United Kingdom. As far as gigs go it was a laborious one, which required me to speak to all eight of Team UK on a weekly basis, collect their thoughts, often rearrange their thoughts, and then remind them at the end of our conversation that I’d be pestering them for more of the same in approximately seven days. They each grew to dislike me, I suspect, but, for a good few months in 2009 we were, at the very least, on first-name terms – Ross, James, Andre, Nick, Martin, Jeff, David and Dean – and propelled by excitement and a shared vision.

This, we believed, was The Start. The start of a journey, an adventure, the start of the United Kingdom’s ascent in mixed martial arts. Indeed, looking back, the blogs reflected this thinking. They were full of positivity and hope, indicative of Team UK’s success on the show, and captured eight UK fighters and occasionally their coach – step forward, Michael Bisping – on the cusp of hitting the big time with the Ultimate Fighting Championship. As a team, they had momentum. They had confidence. They had Ross Pearson and Andre Winner, two of our own, contesting the lightweight final and they had James Wilks making mincemeat of American favourite DaMarques Johnson in the welterweight final. Two plays zero, it was a clean sweep. The floodgates opened. We’d conquered the braggarts of the USA. We’d announced our arrival as a fresh face in MMA. We were proudly defined by Bisping’s wagging finger, cocky snarl and Lancastrian swagger.

But that was 2009.

“I don’t follow it closely anymore,” Wilks, who retired in 2010 because of injury, says from his home in California. He means mixed martial arts, by the way. “I don’t think I was as hungry after the show,” he explains. “I put so much emphasis on winning The Ultimate Fighter that afterwards I was like, oh shit, now I have to keep fighting. For a lot of fighters, fighting is their life. That wasn’t the case with me. I was so focused on winning the show, I knew that would get me a contract in the UFC, but I hadn’t really anticipated going further. I enjoyed teaching people. I still train US Navy SEALs, Marines and law enforcement officers in self-defence.”

“I don’t follow MMA anymore,” says Jeff Lawson, who retired in 2012. “I have a jiu-jitsu team which takes up all of my working time and I simply cannot find time for MMA. I decided to retire because my team suffer when I focus on myself rather than them, and also because I was tired of being punched by fists in four-ounce gloves.”

Though unwilling to call it a retirement, Nick Osipczak, 32, took a five-year hiatus from the sport in 2010, following three back-to-back losses in the UFC, and opted to become an artist in the sacred geometry movement, as well as dedicate himself to Tai Chi. He has fought just once since. “I was aware I was rapidly losing interest in competing with each passing fight and cutting more and more corners in preparation,” he says. “I knew my time competing was coming to an end. The frustration wasn’t from the losses, it was from being in a situation I didn’t fully enjoy anymore but not being sure of what step to take to change things.”

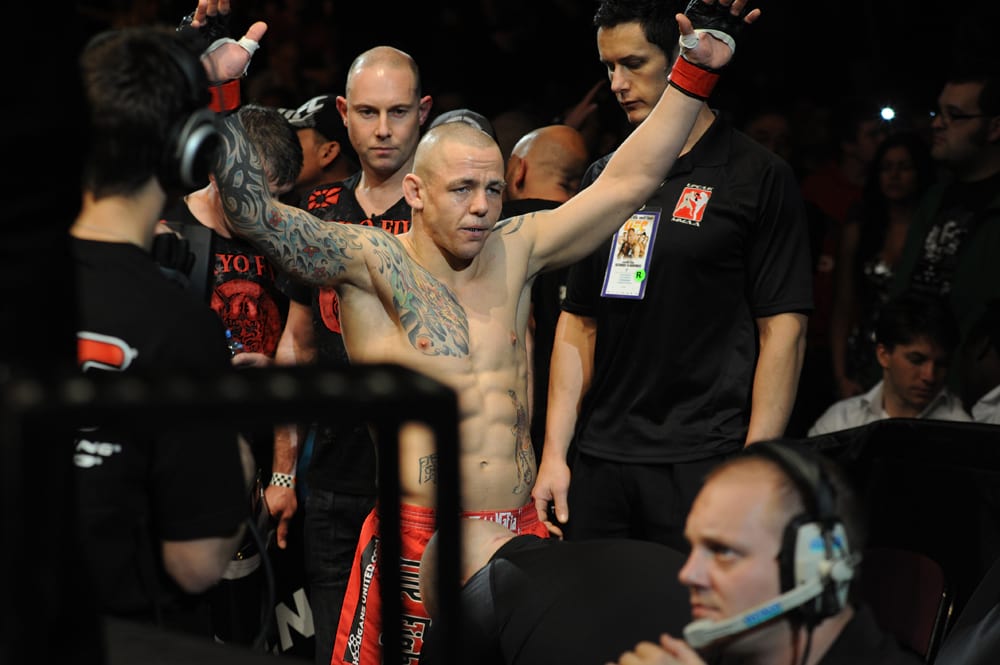

When broken down, the TUF 9 post-mortem looks something like this: of the eight UK fighters who featured on the show only four got the chance to compete in the UFC, and of those four chosen ones only Ross Pearson, the lightweight champion, stuck around. Winner, the striker Pearson conquered in the final, had five fights after the finale and lost three of them, Wilks, the welterweight top dog, had three fights and won one of them, while Osipczak won his first official UFC fight but lost his next three. Pearson, it has to be said, stands alone; he has 21 UFC bouts to his name, an admirable feat in isolation but one which sparkles when contextualised by the misfortunes of his TUF 9 peers.

It would be wrong to suggest nobody saw it coming. Lawson, for one, speaking to me in 2009, said, “The guy that has continually impressed me throughout the process is Ross Pearson. He’s going to be amazing. He’s a top guy and deserves everything that happens to him after the show.” Dean Amasinger, meanwhile, a TUF 9 competitor who would later corner Pearson, said at the time, “He has still got a lot to learn and a lot more experience to gain, but Ross is such a physical talent with bags of potential. His work rate is second to none and his training attitude is impeccable. I haven’t met many fighters more disciplined and hungry and I see his attitude being the thing that will take him a long way. He’s always pushing his body to the maximum, always happy to go an extra round and truly enjoys every aspect of being a fighter. I see him going really far in this sport.”

Pearson was the standout, the one of whom big things were expected, and he has, despite only winning one of five fights in 2016, certainly fulfilled his potential. His run becomes all the more noteworthy, all the more impressive, in fact, when one recalls the Brit-heavy landscape circa UFC 105 (November 2009), otherwise known as the night the nation peacocked before the eyes of the world, sent our troops into battle and celebrated seven scalps on a single UFC show. Count them up. Andre Winner beat Roli Delgado, Nick Osipczak beat Matthew Riddle, Terry Etim beat Shannon Gugerty, John Hathaway beat (fellow Brit) Paul Taylor, Ross Pearson beat Aaron Riley, Dan Hardy beat Mike Swick and Michael Bisping beat Denis Kang. I mean, for a moment, if only a fleeting one, it seemed Great Britain – specifically, the Manchester Arena – was the very centre of the entire mixed martial arts universe.

“That night felt amazing,” says Osipczak, “and it was also special because the Rough House became the first team to get four wins on a UFC card on the same night. I can still remember the 17,000 fans chanting my name. That really gave me an extra boost of energy during the fight.”

For Wilks, however, memories of UFC 105 are less rosy. With 18 pounds of water weight cut during fight week, he remembers feeling tired after round one of his bout with Matt Brown, utterly spent by round three, and then eventually stopped by punches with less than three minutes to go. It resulted in the first defeat of his UFC career. A year later he had his last fight.

“I did want to do well for myself, but also for the UK, to represent,” Wilks remembers of that time. “I felt like the UK wasn’t that well-represented in the UFC and I wanted to show that a British guy could do just as well as anyone else. There was massive adrenaline when I came out in front of a sold-out crowd, but after a couple of fights you start getting used to it and then after a couple more I felt I was going too far the other way. I became too relaxed.”

The likes of Jeff Lawson, Dean Amasinger, David Faulkner and Martin Stapleton were innocent bystanders that night in Manchester. They witnessed the British takeover from afar and knew, nay, hoped that if the momentum continued they too would be in position to capitalise in the coming months and years. After all, everything, they were told, was improving; better wrestling, better jiu-jitsu, better gyms, better coaches; more UFC events in Europe, more attention, more opportunity.

“Part of me is disappointed I didn’t get very far, but I think my life would be totally different if I had,” says Lawson, 38. “It would’ve certainly gone to my head and I’d probably be slumped over a blackjack table in a casino telling people how awesome I was at fighting and showing them my trophy wife. As it is, my life is perfect. Everything has worked out and I wouldn’t change what happened for the world. I think I would’ve been easily forgotten had I just done a UFC match instead of The Ultimate Fighter.”

Here’s the thing: back then, around 2009, The Ultimate Fighter carried gravitas. It meant something, resonated with fans, supposedly led somewhere. It’s different today. Sullied somewhat. It has lost its purpose; perhaps, you could argue, it now has a different purpose. But those early incarnations, particularly TUF 9 and the rise of Team UK, represented seminal points in what we perceived to be movements. It’s why cast members carry fond memories to this day.

“I remember a lot from the show and the overall feeling is a good one,” says Osipzcak. “The novelty of staying in a mansion and being chauffeured everywhere is probably what stood out the most.”

“It’s one of the key moments in my life,” says Wilks. “It has been surpassed by having my own kids, but it’s still the best personal accomplishment I have, certainly athletically.”

“There was a huge sense of family and we were really taking care of each other and having fun,” says Lawson. “On the whole it was a hugely positive experience, and life after the show was just surreal. We were doing interviews all over the country and abroad; getting recognised in the street was awesome but very, very strange. My entire life has been built on the reputation of being on The Ultimate Fighter. Because of it, I have a wonderful gym full of talented, like-minded people. The Ultimate Fighter has been a marketing dream.”

If anything, TUF 9 perfectly captured a moment in time. One for the underdogs, it served to rework a misconception that the UK couldn’t compete with the MMA superpowers, and Wilks, an ex-rugby player educated at Bournemouth University, using impressive jiu-jitsu to tap out an American in the welterweight final was a microcosm of this.

“I was walking out to the finale thinking, oh man, I probably shouldn’t have opened up a gym these last couple of months,” says Wilks, 38, who moved to the US in 2000. “I thought that was a mistake. I thought, I’m probably not going to win.

“I remember when DaMarques Johnson up-kicked me in the head I was semi-conscious, so I sat back for a heel-hook and it didn’t work and he got on top and I thought, oh well, I got this far, that’s pretty good. I really thought I had lost. All fighters say, ‘I knew I was going to win.’ I didn’t. I just kept pushing through. It somehow worked out for me.”

The last time the UFC were in Manchester, England it was October 2016 and the event was headlined by Michael Bisping’s UFC middleweight title defence against Dan Henderson. There were wins for Bisping, Jimi Manuwa, Marc Diakiese and Leon Edwards, a shot in the arm for British MMA, if hardly one of UFC 105 proportions. But, above all else, UFC 204 was a coronation night for Coach Bisping, the 38-year-old who is still, eight years on from The Ultimate Fighter and his Brit Pack, very much the face of British mixed martial arts and its most successful exponent. And that, in itself, says an awful lot.

“I didn’t think much of Michael Bisping before The Ultimate Fighter, but, when I got to meet and train with him, he was a lot better than I thought,” says Wilks. “I knew he’d do well. I didn’t think he’d do as well as he has, though. I guess he just kept improving and getting better with age. How has Bisping done well? He came to the States. How did I do well on TUF? I trained in the States. The training has got much better in the UK, but wrestling, for example, can never be close to the wrestling here.

“When I left in 2000 Maurício Motta Gomes was the only black belt in the whole of the UK. I rolled with UK fighters in 2002 and 2003 and their jiu-jitsu was terrible. But then, when I got on the The Ultimate Fighter and rolled with the UK guys on the show, I was like, wow, they’ve really come along. I thought, in terms of MMA, the UK would be up there with the other countries by now, but they are not even as well-represented as they were when I was competing. Perhaps the rest of the world has improved as well.”

It’s 2017 and the United Kingdom is still, as a fighting nation, defined by Michael Bisping’s personality and success. He’s still very much Coach.

*** This feature originally appeared in the May 2017 issue of Fighters Only magazine ***